Vanlife diaries #53: Oaxaca de Juárez, Hierve el Agua & Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca Mexico

Last Updated on 4 January 2024

We’ve spent the last several months listening to foreigners and Mexicans alike saying that their favourite place in the entire country, the “best of everything” that Mexico has to offer, is Oaxaca. No other city or state has received even a fraction of this hype, nor such consistently glowing reviews, and we couldn’t help but feel a mounting sense of expectation as we travelled south towards Oaxaca— one that I feared no place would actually be able to live up to.

This week, we finally made it to this beautiful south-central Mexican state and discovered for ourselves that Oaxaca is deserving of ALL the excessive praise and unprecedented hype, and then some. We’ve been sold no lie— this truly is the best of Mexico.

Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca

Cruising down from Puebla, we enjoyed a rare moment on the smooth toll roads— something we have only done one other time in Mexico because of the rather substantial expense (nearly $20USD for this particular journey), but which saved us more than 2hrs as we crossed statelines.

As we’d learn, Oaxaca has some of the worst road conditions we’ve encountered in Mexico, and it was a true blessing to avoid at least some of the potholes and surprise topes (speed bumps placed by a crazy person at random intervals along the Highway, rarely marked and seemingly designed to destroy your shocks).

Our first stop in Oaxaca was to Cervecería La Cura, a brewery just outside of town, and then into a very glamorous supermarket parking lot, but the real excitement began Saturday morning as we journeyed into the city centre and left our van safely parked within a secure estacionamiento owned by a wonderfully kind Mexican family.

Over the next several days, we’d return to the parking area each night and be greeted excitedly by Julio and Ciro, who chattered in broken English and poured generous servings of mezcal for their first foreign visitors in quite some time.

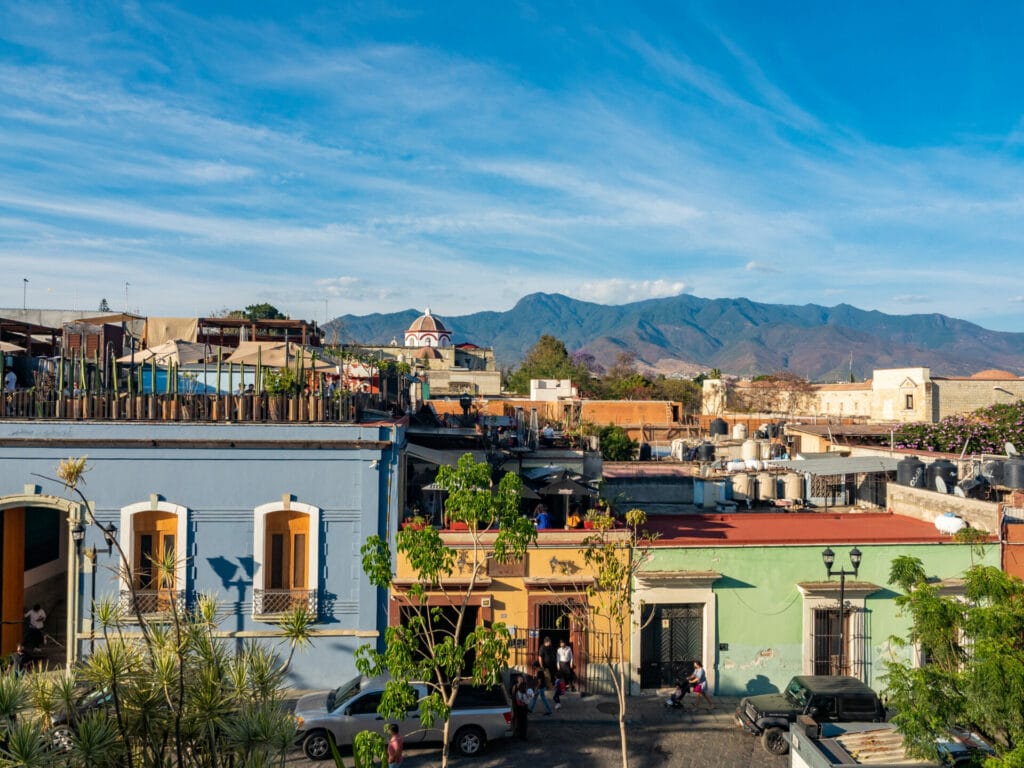

Immediately, we were delighted by the kaleidoscope of Oaxaca, every market packed full of naturally dyed rugs and vibrant green pottery, the streets and shops brightly painted and a palpable feeling of excitement dripping in the not insignificant winter heat.

What we didn’t know at the time— but would learn soon enough— was that today was Carnaval in Oaxaca.

A massive parade stocked by 13 of the surrounding pueblos took over the city streets in the afternoon, intercepting our path as we navigated between Mercado Benito Juárez and the cobbled Zócalo.

Among the women dressed in traditional skirts and adorned with colourful hair ribbons, enormous paper-mâché heads floated by atop half a dozen other participants and several full bands, spaced out between several hundred people, beat a constant rhythm to drive the parade forward.

Young men wore wooden masks painted to look like the devil, cow horns protruding grotesquely from the side and straw hanging limply underneath to give the appearance of hair.

Cow bells on their waist kept constant rhythm, and as they flounced by, hands whipped quickly from their pockets and a flurry of flour and confetti covered my head— we were part of it now.

Others wore bright red robes and carried a handful of dowels topped by painted eggshells, which they handed out to women in the crowd as they sauntered past.

Men in Halloween masks cracked whips violently against the pavement, somehow managing to avoid hitting any onlookers despite their somewhat deranged fervour.

But perhaps most curious of all were the men covered head to toe in motor oil. By the time we’d marched to the terminus of the parade, bands still playing to the raucous crowd of confetti-covered dancers, these greasy black hands would grab at your face or your arm and leave you marked by the devil.

Naturally I found myself, with an unrestrained smile and large camera, to be an easy target— soon my face and arms were covered in oil, a souvenir of the evening that seemed to earn me respect among the locals as we all danced under the trees.

More than a few shots of mezcal were handed our way, some from expensive glass bottles purchased in town and others from plastic jugs, moonshine mezcal made in the hills and brought into the city for just such an occasion.

Stumbling into Carnaval was an unbelievable introduction to Oaxaca, a city known for its rich tradition and unrivalled festival spirit— if we couldn’t be here for Día de Muertos, Carnaval had to be a close second. And it had unfolded before us purely by chance, a wild evening surrounded by all the colour and culture we’d been promised in Oaxaca.

We spent our next several days wandering around the city soaking in even more magic. This included several rooftop bars, candlelit mezcalerias, and even a mole and mezcal pairing class run by a certified mezcal sommelier.

Sampling each of Oaxaca’s 7 traditional moles alongside 7 of the most popular maguey (agave) varieties used to produce mezcal, we deepened our appreciation for the complex beverage— which would become a focal point for our exploration of Oaxaca state later this week and well into the following week.

We visited far too many amazing restaurants and fantastic distilleries to recount in this weekly update, but after a solid chunk of time in Mexico’s most beloved city, I will certainly be working on a travel guide in the coming months— stay tuned!

Our final taste of Oaxaca was participating in a temazcal just outside of the city, something I’d been particularly looking forward based on my interest in both Zapotec culture and profuse sweating (who doesn’t love a good sauna?!).

Meaning “house of heat” in Nahuatl, temazcal is an ancient sweat lodge tradition that has been practiced by local indigenous communities for thousands of years as a means of spiritual cleansing and connection to Madre Tierra (Mother Earth).

Our first experience with this ritual was at Temazcal Oaxaca, where we arrived in the afternoon into a magical little garden, sipping mezcal and listening to gentle pan flute music before we crawled inside the circular brick temazcal.

Once inside, the temazcalera placed enormous bundles of fragrant herbs directly on the coals until the entire dome smoked with pirul and lavender. She explained that Zapotec people viewed temazcal as a sacred womb— warm, dark, safe, and completely transformative, such that exiting the temazcal after a proper cleanse is like being reborn.

We had a great time sweating all of our worries away in the temazcal, but I couldn’t help but feel that the experience had lost some of its spirituality and authenticity in order to cater to tourists. The following week, after stumbling across another temazcal hours outside of the city, I’d finally experience that “rebirth” I’d been promised.

Hierve el Agua, Oaxaca

Located about 70km east of the city and among Oaxaca’s most popular tourist attractions is Hierve el Agua, a truly astounding geological feature in the Sierra Madre del Sur that has been a sacred site to local Zapotec people for thousands of years.

Translated from Spanish, Hierve el Agua means “the water boils”, a reference not to hot springs (as I had assumed) but to cool fresh water that literally bubbles up into the rock pools.

This water, naturally high in minerals, trickles over the limestone cliffs— and just as stalactites form in caves very slowly as mineral water drips from the ceiling, this “petrified waterfall” is the result of slow and continuous calcium carbonate deposits.

Against the backdrop of lush green hills and rolling agave fields, you can’t imagine a more magical vista, nor a more surreal environment.

A couple years ago, Hierve El Agua closed to the public with no immediate plans to reopen— many cite the pandemic as the obvious culprit, while some have suggested that the closure was actually a response to the imminent threat of over-tourism and others believe it’s related to conflict between the small local villages in the area.

The main Highway accessing the site also closed, and although we had a good idea that Hierve El Agua had re-opened this year based on recent photos online, we had no idea about this access road— and were constantly given conflicting information about the status, including the Oaxaca Tourism Office who insisted adamantly that there was no alternate road and therefore the site was effectively closed.

What’s more, we were also told there might not be water this far into the dry season, so there was a question as to whether a several-hour detour would really be worthwhile…

All this to say that it took a great deal of research, a long rough drive up the loose dirt mountainside through Xaaga (the alternate and only current route available), and a bit of blind faith to make it to Hierve El Agua.

But when we did arrive and pull into our campsite overlooking the natural rock pools below, there’s no question it had been worth it.

Since we were spending the night and every single other person at Hierve El Agua was day-tripping with their family (Mexicans) or part of some rushed group tour (gringos), the security allowed me to stay after closing and I eagerly romped through the entire area in search of the best photo angles.

More than a few times, a passing tourist would complain about the need to rush back to their minibus so soon, which only left me feeling more satisfied to be here with our own transport and free to stay as long as we’d like. Yet another van perk!

My exploration through Hierve El Agua included a dusty and steeper-than-bargained-for hike in my Birkenstocks to a viewpoint below the falls, as well as up and around all 3 of the pools that are currently filled— indeed, the site was not at its normal water levels, but I was happy to be there nonetheless.

After a torrent of sunset photos, I returned again in the early hours of the morning (in an attempt to beat the crowds, while Dan still slept) to explore even more of this beautiful site.

Naturally, this included a swim— despite being about 30C at 9am, I still drew plenty of strange looks as I splashed around in the cool water so early in the morning. I’ll never complain about having the pool to myself, though!

When Dan finally joined me, we repeated the dusty hike I’d done the previous day, but completed it as a loop through the cactus and wild agave below Hierve El Agua.

Despite the popularity of the site in general, we were the only ones on the trail— all the better to appreciate this wild and wonderful landscape.

Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca

We wrapped up the week in Mexico’s primary mezcal region— just an hour from Oaxaca City, the little town of Santiago Matatlán produces over 70% of the state’s mezcal (which in turn produces 90% of the world’s mezcal) and is one of the best places to learn about this 2,500-year-old beverage.

Like many others, before spending time in Oaxaca, I just thought of mezcal as a “smoky tequila”.

And technically speaking, tequila IS a type of mezcal— produced exclusively with blue agave that grows in Jalisco and several surrounding municipalities on Mexico’s pacific coast— and at one time, it was produced entirely by hand in the same way as mezcal. But the comparison pretty much ends there.

While tequila can only be made from one type of agave, mezcal can be produced from over a hundred different agave varieties— each incredibly complex and nuanced, most of them growing wild in the mountains of Oaxaca, and none of them producing a smoky flavour (if the predominant flavour is smoke, it’s not a good mezcal!)

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that mezcal is the most diverse and variable spirit in the world, and now that we’ve visited about a dozen palenques (mezcal distilleries) and seen firsthand the respect and passion that mezcaleros have for this ancient liquor, it also seems the most special.

Who doesn’t want a drink with a centuries-old backstory?!

In many ways, Santiago Matatlán is similar to Tequila, the charming pueblo mágico we visited a few months ago in Jalisco (home, as you may have guessed, to tequila), every second shop a distillery and the entire landscape dominated by agave fields.

And just as Tequila offers a more authentic tasting experience than nearby Guadalajara, so does a trip to Santiago Matatlán provide a far greater appreciation for mezcal than does Oaxaca City.

But the production of tequila is notably different than that of mezcal, and it’s readily apparent when you visit these two regions— where tequila was commercialised several hundred years ago and is now predominantly produced and distributed by enormous distilleries with expensive equipment (think Casa Souza and Jose Cuervo), mezcal is still hecho en mano.

This is an enormous source of pride for Oaxaqueños, many of whom see tequila as a “sell out” for reverting to commercial production methods.

Santiago Matatlán is instead home to a seemingly infinite number of small, family-operated palenques that have safeguarded the tradition of ancestral mezcal production.

As we’d learned of pulque previously, mezcal has thousands of years of history in pre-Hispanic Mesoamérica and was regarded as a sacred beverage— but fell firmly out of fashion for many generations. Mexicans weren’t interested in drinking mezcal, nor were foreigners really aware of its existence, until quite recently.

Presently, mezcal is in the midst of a renaissance. Distilleries are flourishing as public interest turns back to this ancient spirit, and with mounting export to the US, Australia, and Europe, the world is slowly discovering the magic of mezcal.

We saw the evidence of this firsthand in Matatlán, where most palenques we visited were operated by 3rd or 4th generation mezcaleros, but the brand itself was only established within the last decade— families have been making mezcal seemingly forever, but it’s only recently become a viable business.

We tasted mezcal at a number of spots around Santiago Matatlán this week (and even a little into next week), but our favourite experiences were touring these palenques— small, family-owned mezcal distilleries that open their doors to show interested visitors their process and share the magic of this ancient spirit.

Our favourite among these were Gracias a Dios and Mezcal Macurichos, both of which make truly excellent mezcal from a wide variety of wild agave.

We watched as a horse drove a wheel around a stone dial to crush the agave, saw heaping piles of dirt steam as the agave cooked beneath for 6 days, observed the rudimentary distillation process dripping through copper-lined clay pots, and even tasted the 80% alcohol that emerged from the small metal spigot.

Everything was incredibly simple, entirely harvested, cooked, distilled, and bottled by hand, and yet there was an overwhelming respect and understanding for agave— at its core, mezcal is a deep part of local culture rather than just a means to get drunk.

There are no gatekeepers to mezcal production either, and a vast majority of the mezcal we’ve encountered in Mexico is made by “so and so’s uncle” with no technical equipment and hardly more than a small backyard.

You don’t need a lot of money or space or business savvy to produce mezcal, you just need knowledge (handed down from your abuelos, most likely) and patience— and so it seems that every family in Oaxaca is making their own mezcal, some better than others, but all according to traditional methods that importantly forbid the addition of anything artificial and instead aim to accent the unique taste of each agave. This would be just the beginning of our experience with mezcal.

Where we stayed this week

- Parking outside of a Soriana supermarket in Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca (free; 4 Mar)

- Camping in secure overnight parking in Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca (600p for 3 nights; 5-7 Mar)

- Parking outside of our temazcal house in Santa María Coyotopec, Oaxaca (free; 8 Mar)

- Camping above the waterfall at Hierve el Agua, Oaxaca (100p; 9 Mar)

- Parking at the Gracias a Dios Mezcal Palenque in Santiago Matatlán, Oaxaca (free; 10-11 Mar)

- Airbnb in Lachigolo just outside of Oaxaca City ($180 for 3 nights; 12-14 Mar)